Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

Terry Watada is a poet, novelist, short story writer, historian, playwright, columnist, essayist and music composer. He has published five poetry collections, three novels, a short story collection, two mangas, two histories on the Buddhist Church in Canada and two children’s biographies.

His published titles include The Game of 100 Ghosts (Mawenzi House, Toronto 2014), The Three Pleasures (Anvil Press, Vancouver 2017), The Four Sufferings (Mawenzi House, Toronto 2020), and his third novel, Mysterious Dreams of the Dead (Anvil Press, Vancouver 2020).

Terry Watada was awarded both the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal and the National Association of Japanese Canadians’ National Merit Award in 2013, and the Dr. Gordon Hirabayashi Human Rights Award in 2014.

The Monitor sat down with Watada this spring to discuss his work and his reflections on the 80th anniversary of Canada’s internment of Japanese citizens, which quietly passed on January 16, 2022.

The Monitor: You retired in 2012 and then began writing poetry and fiction. In the ten years since you’ve retired, you have published three novels. Your fourth novel, Hiroshima Bomb Money, has just been edited. You’re working on a new play for the Lighthouse Festival Theatre in Port Dover. And you are compiling your sixth poetry collection around your award-winning piece, Masks. If I could start with one question for you, I think it would be: how? And a follow up question: is it still called retirement if you are publishing this much?

Terry Watada: Well, retirement from being an educator, I guess. But that’s not true either. I strive to educate through my work. You’re right. It’s not retirement. I just have a different career, a second one. What did F. Scott Fitzgerald say? There are no second acts. So maybe it’s all part of the first act.

I have a literary agent for Hiroshima Bomb Money, which is new. The other novels I did on my own, trying to get published, so it’s being shopped around right now to various publishers. And we’ll see how that goes.

It’s interesting timing because of what Putin is doing, threatening nuclear war, because, of course, my novel looks at the effects of nuclear war. In fact, it looks at the effects of war in general on three countries: Japan, China and Canada. So it seems the timing is right.

M: When you look at the breadth of work that you’ve produced over the last decade, what is it about these narratives that inspired you to create such a profound body of work?

TW: I think that mostly it’s the people—Japanese Canadians, especially seniors— who approach me and tell me stories about their past. I seldom go up to someone and say, “hey, tell me about such and such.” They volunteer these stories. I find it so fascinating and I have to honour them by putting their stories in some kind of form—whether it be a play or a novel or a poem. Also I have to honour my parents as well.

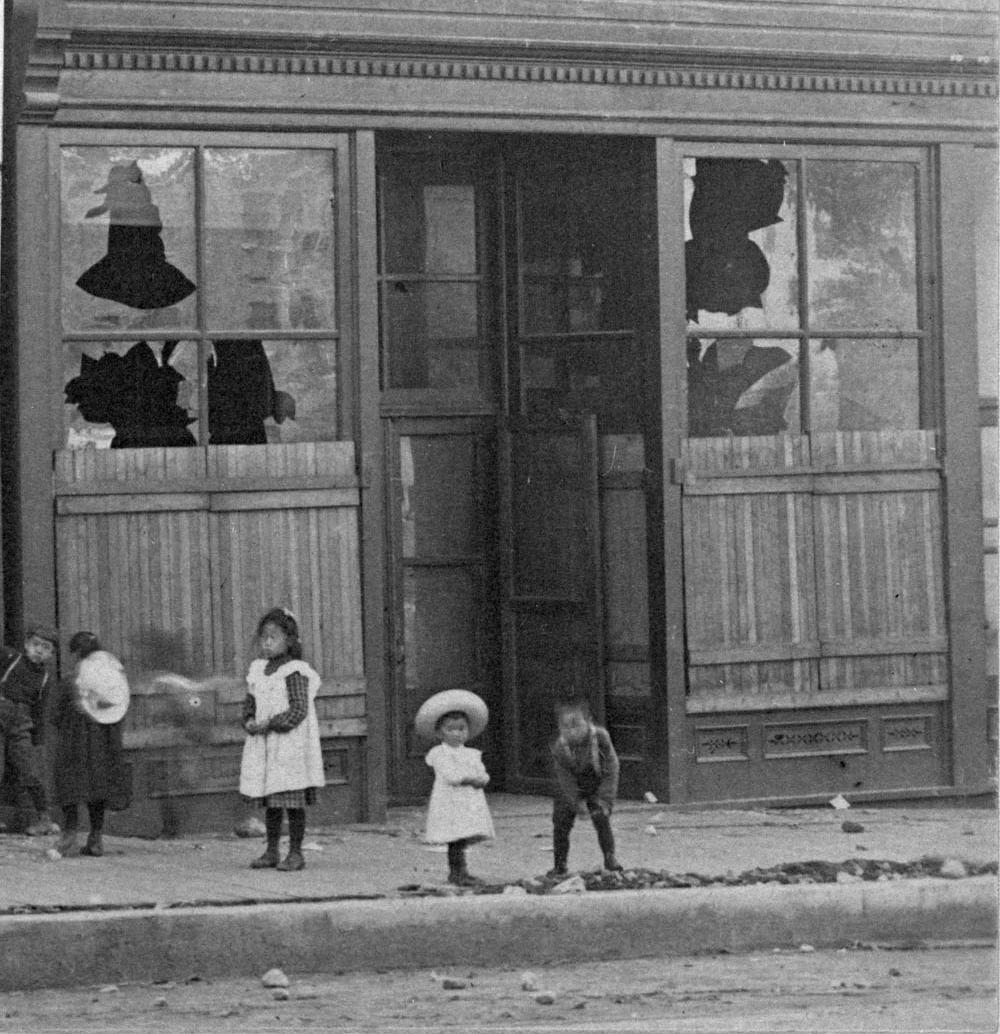

M: This issue of the Monitor examines the rise of right-wing extremism in Canada. When I was examining how the occupation of Ottawa played out—particularly how politicians and residents responded to the violence, the flying of Nazi and Gadsden flags and the terrorizing of entire communities—I saw a lot of similarities between this event and the 1907 race riots in Vancouver. Specifically, the responses often focused on Canada’s reputation being tarnished, but not specifically being upset with the overt racism on display. And we know that 35 years after that initial race riots in Vancouver, there were prevailing racist attitudes towards Japanese Canadians that allowed for the creation and operation of internment camps. As someone who has warned about the fragility of our democracy, I’m wondering if you have any thoughts about the recent occupation and ongoing Freedom Convoy protests that are happening in Canada?

TW: Back in 1907, the riots were inspired by Reverend G.H. Wilson, whose grandson, Halford Wilson, was a councilman for Vancouver. He really had a virulent hatred of Asians—Japanese Canadians in particular. And so the riot initially started with the reverend standing up and saying that he’d envisioned a white Canada. He didn’t want to have any Japanese or Chinese or any other foreigners in this country. So it sort of gives this sheen of religious Christian fervour that gives it credibility. And people went along with that. So when you bring it to the present state where the convoy happened and the occupation took place, it seems there’s a parallel there where the undercurrent seems to be. We’re doing it for the just cause of freedom, as it were. They called it freedom, you know? It just seems preposterous to me.

“

There’s a stereotype… that Japanese Canadians were very co-operative [during internment], that they just accepted everything, they left and they wanted to be forgotten about.

M: I want to focus on your experience with learning about and then capturing oral histories of internment. You’ve said that your family’s experience was shrouded in “a conspiracy of silence” but it certainly feels like that description could apply to this entire chapter of Canadian history. Aside from black-and-white photos in the National Archives and the City of Vancouver Archives, there isn’t a lot of information or understanding about what happened during this period. Can you share a bit about how you came to make sense of this history?

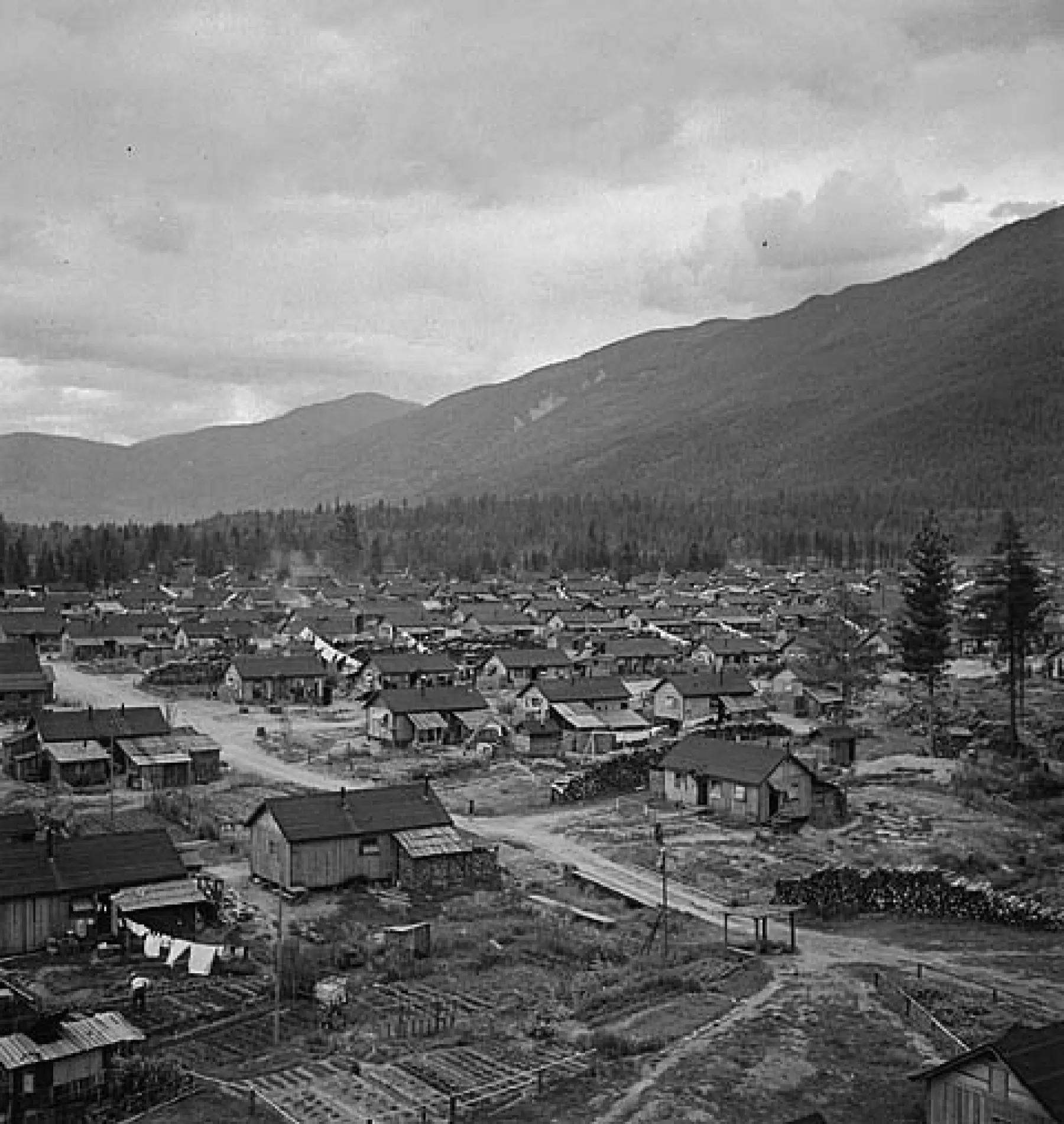

Internment Camp, Lemon Creek B.C. Photographer: Jack Long. Reprinted courtesy of Library and Archives Canada, Item ID 3623175

TW: As I’ve said, in 1970, I saw those photographs for the first time at a conference. Before then, I hadn’t realized that the internment had even happened. And I went to my parents and asked them questions. Of course they spurned me and turned me away and said, “You don’t need to know that stuff.” But I kept at it because I started to realize that Japanese Canadians didn’t get the vote until 1949. I was born two years later.

So I could have been a non-citizen citizen at one point. That frightened me. I thought about the significance of that. It drove me to find out more stories and then I started hearing stories from everyone. It’s just that those stories are not generally known, as you said. But if you go to the Powell Street Festival in Vancouver, you’ll hear people talking about it, or at least in certain moments.

And that inspired me because these were human beings that were put through this terrible experience. There is a stereotype now and it’s generally thought that Japanese Canadians were very co-operative [during internment], that they just accepted everything, they left and they wanted to be forgotten about. But in hearing the stories, especially about the protests, I realized that these were people with feelings. They weren’t just people that readily accepted what had happened and obeyed the government, like a stereotype demands.

That’s how I got more and more involved in collecting stories and listening to stories. There were also—well, they’re still going on today—the internment camp bus tours, which were first organized in the 1980s. I went on a couple of them. It was emotional because the victims were there, going back. I don’t know if they were trying to recapture the past, but they were there and many of them started crying because of the memories flooding back to them. And they spontaneously started talking, telling tales of that internment experience. So I learned a great deal from that. And I took it from there. I started compiling and then writing the stories.

M: You’ve mentioned previously that your writing for The Three Pleasures began with the story of the Nisei Mass Evacuation Group. Can you share some of that story and why it was an important place for you to start?

TW: Yes. At the time, it was all chaos. My own father was kidnapped. I call it kidnapping. The RCMP took him away and put him in a road gang in the eastern side of B.C. it turned out, which is something, because I didn’t know that until recently. I knew he was taken away, but I didn’t know exactly where, and they didn’t tell him where he was going. They didn’t tell my mother or my brother. They just took him away.

An RCMP officer checks documents of Japanese Canadian men on their way to internment camps, circa 1942. Photographer: Tak Toyota. Reprinted courtesy of Library and Archives Canada, Item ID 3193862

The Nisei Mass Evacuation Group said, why are you breaking up families? Especially when the formal announcement of the internment came about, this group of Nisei decided to negotiate with the government. So they tried with the B.C. Security Commission and said, let us go with our families. Don’t put them into dire straits by separating us. But the government wouldn’t listen. The Nisei kept trying to negotiate.

Out of that came another group called the gambariya, a resistance group who actually wanted to fight, wanted to protest. And they did stage a protest in Vancouver and they were all taken to a place called Angler—actually, first to Petawawa, which had a concentration camp where a lot of German and Italian prisoners of war were. And so the Petawawa camp had this whole section of Japanese Canadians as well.

471 Niseis and 295 Isseis aged 17 to 60 were held captive in a remote POW camp at Angler in northern Ontario. Reprinted courtesy of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre Archives

Very little is known [about that camp]. One thing that I found out was that there was a doctor there in Petawawa who was encouraging second-generation Japanese Canadians to cooperate. And the gambariya didn’t like that because they had to be together to stage protests. So they visited him one night in his cabin, but he wouldn’t back down. They told him, you have to stop this. We have to be together to show a united front. Because he wouldn’t co-operate, they started beating him, which caused a lot of noise.

Of course, the guards immediately thought that an escape was going on. So, they opened fire on the Japanese cabins. The men in those cabins saw what was going on because the search lights went on when they started shooting and the men rolled onto the floor and out of the way, but bullets hit their beds and pots and pans. I put [that story] in a novel, because I think those stories have to be told.

There are other protests along the way. I found out that after World War II, the government tried to gather everyone moving east of B.C. and west from Petawawa and Angler, and put them in Moose Jaw, in an abandoned air force base. And from there they would go to various locations across the country except BC, of course. And the gambariya group, the remnants of it, refused to leave and staged a two year protest there after the war.

They had hunger strikes. They had demonstrations while they were in camp. And finally, when the Canadian government kicked them out, most of them went on to other places, but two of them did a sit down strike in front of the air force base and they stayed for, I think, two months protesting. Those guys were tough. You know what I mean? They were given support by townspeople, a nice tent, some food and sleeping bags. They stayed until they couldn’t take it anymore and left. I met one of those guys. By that point he was settled into Lethbridge in Southern Alberta. He was very bitter and I can understand that.

So he made me aware of the whole situation and made me want to write about it.

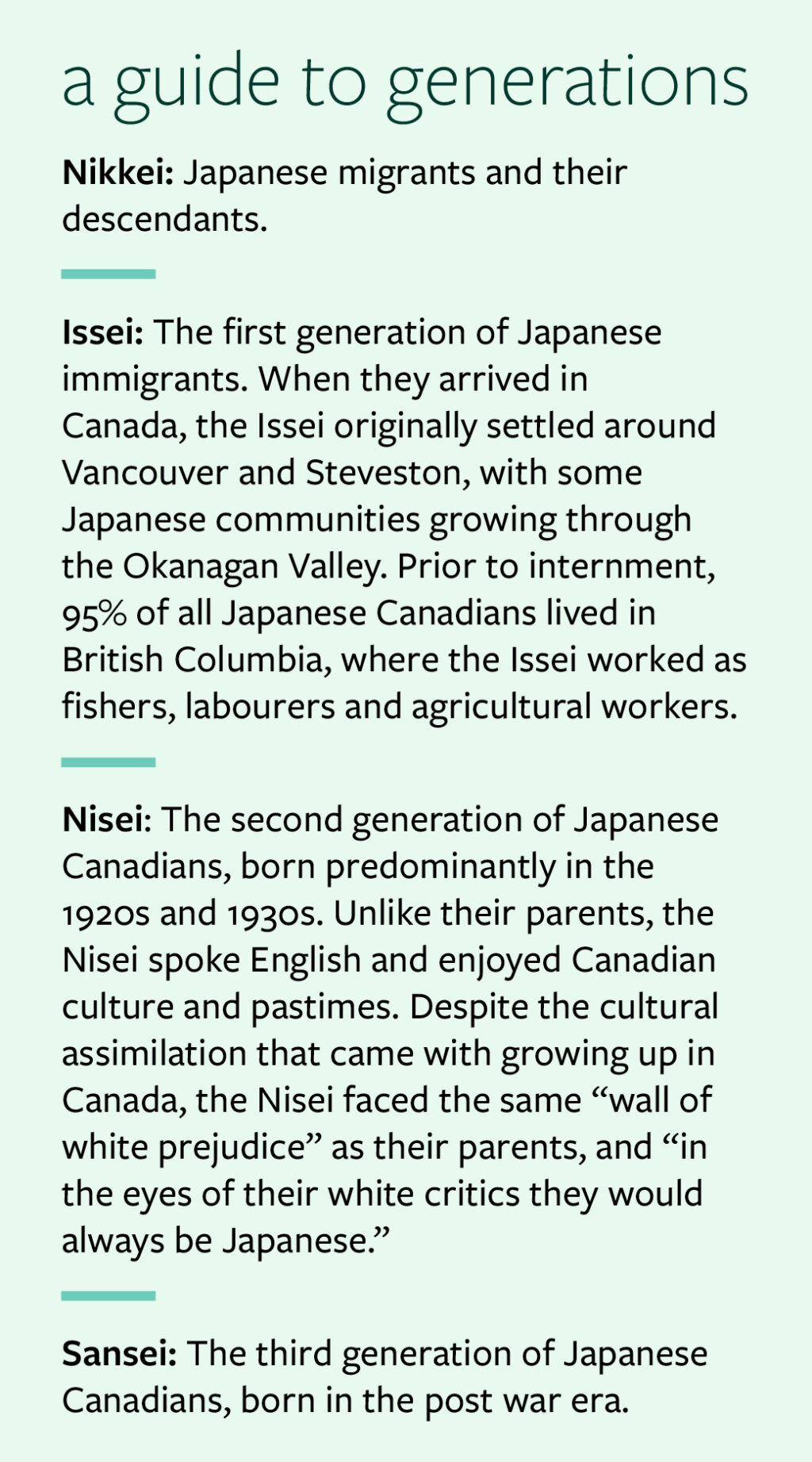

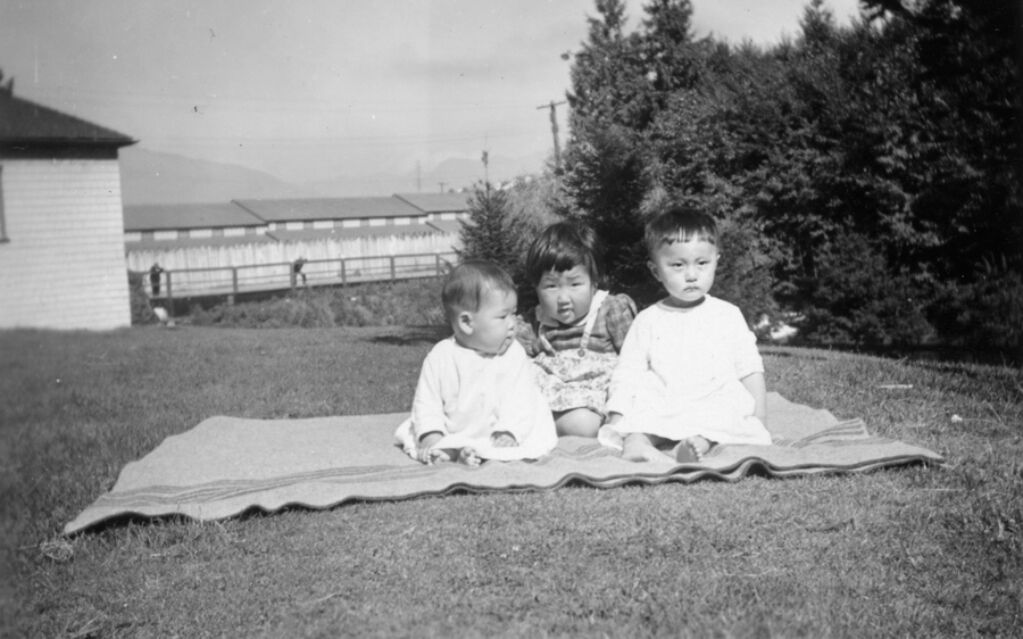

Children and babies requiring medical attention at Hastings Park were kept separate from their mothers. Photo courtesy of the Nikkei National Museum, ID 1996-155-1-21

The fourth novel, Hiroshima Bomb Money, I don’t think the Japanese government’s going to like me very much. But that’s okay. It’s not my country.

I also found out something new [while working on Hiroshima Bomb Money] because I think that with every book I produce or work on, there has to be something new to the internment story.

I found out that in Hastings Park—which was the distribution centre in Vancouver for all of the Japanese Canadians who lived outside of Vancouver—whenever a baby became sick, they were separated from their mothers. They were actually just taken away from them.

And since many of the mothers couldn’t speak English they didn’t know what was happening. The doctors, the nurses just ripped them away and took them. They probably explained what was going on in English, but they couldn’t understand. The babies weren’t properly treated. They either lived or they died. And if they died, I’m not sure if they told the mothers, you know? It is quite inhumane. When I learned this, I saw the parallel with the situation on the Southern border of the United States, where they were separating kids from their parents.

M: You’ve talked about the hesitancy of Japanese Canadians to share their internment experience, with not wanting to burden their children with the knowledge of their experience. How did you overcome that hesitancy to record the oral histories that make up your project, Wasteland Gardens and provide the research for your novels?

TW: Pestering. I kept at it, just asking and asking.

The redress also helped a great deal to unlock that silence. People started talking after it. There are still people today that won’t talk about the past, but there are others who are willing to tell their stories.

My wife has observed that people just volunteer their stories to me. As I said before, I don’t prompt them. They just start talking to me. When I wrote the Buddhist church book, those meetings were three to four hours long, but most of that time was taken up with telling stories about the past. I think given that situation, they felt comfortable. There’s no jeopardy in telling these stories. So they come forward. They seem to want to unburden themselves and here is a perfect situation to do that.

In general, they won’t tell their kids and they won’t tell what they would call their Canadian relatives. And by that, I mean, their white relatives. It’s interesting. My mother always called our [white relatives] Canadians and we were Japanese. So they wouldn’t talk about the past with them, as if it was some sort of shame they had to hide. But given the right circumstances, they will talk to me. My wife has always astonished by this.

Japanese Canadians prepare to depart to internment camps, circa 1942. Photographer: Tak Toyota. Reprinted courtesy of Library and Archives Canada, Item ID 3379268

M: You recorded Wasteland Gardens almost 35 years ago. How long did it take to record and compile all of those stories in a pre-digital age?

TW: The internment tours I mentioned before helped. I heard a lot of stories and I wrote them down and later on, I would ask if I would tape them. At first [participants] were hesitant. But I told them that I wouldn’t make the recordings public. So they were open to that. But it must have taken about a decade, I guess. And I’m still doing it, actually. So ever since Wasteland Gardens, and even 10 years before that, so for 45 years now telling these stories.

If I go back to include writing music as well, that was the early 1970s. When I was no longer in a rock and roll band, I decided to try writing my own songs and fortunately I found that there was an audience for it. I started to write songs about my parents’ experiences, my friends’ experience and their families’ experience as well.

When I travelled down to the United States and was performing, I noticed that my audiences were Asian American rather than just Japanese American. It was a perfect example of the second, third, fourth generations coming together because of shared experiences, the common issues that linked us together.

“

Canadians don’t want to bring this issue up because it’s painful. It’s shameful. It’s a total embarrassment to them. But how else can we learn?

M: On February 24, 1942, the government led by Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King issued the order that would lead to the internment of 90% of all Japanese Canadians (21,000 people). Despite this measure having sweeping implications for an entire population, it is a largely forgotten chapter in Canadian history. In previous interviews, you’ve highlighted that Canadian high schools typically devote a single hour to learning about internment, which, given the complexity and far-reaching implications of the policy, seems profoundly inadequate. The commonly understood story seems to have been reduced to one where internment temporarily moved a community to a different location. As this moment in time feels further and further away for young people, how would you recommend situating this history to maintain its relevance and to impress the urgency of its lessons?

TW: I think if there’s an issue like the demonstrations in Ottawa and across the country, when those come up, people should point out that this has happened before.

First of all, bring it up and link it to what is going on in the present day. That keeps the issue of internment alive. And I think there’s also been an explosion of literature about the internment. I’m not speaking about myself in particular, but several authors who have brought the issue forward.

If scholars can tap into that, this is how to keep it alive. As for the school boards, they’ll do what they do, you know? Unless there’s pressure put on them by groups who want to add more to the curriculum about Japanese Canadian history, [it won’t happen].

M: I think I mentioned to you in our earlier conversations that there is a single book in the Ottawa Public Library that covers the 1907 riots or the internment. When I saw the catalogue I thought, “Oh, we have a problem.”

TW: Yeah. Well, I understand. Canadians don’t want to bring this issue up because it’s painful. It’s shameful. It’s a total embarrassment to them. But how else can we learn? How can we learn and to prevent it in the future without knowing what happened in the past? Things like the Ottawa Convoy and what underlies it are disturbing and have to be dealt with.

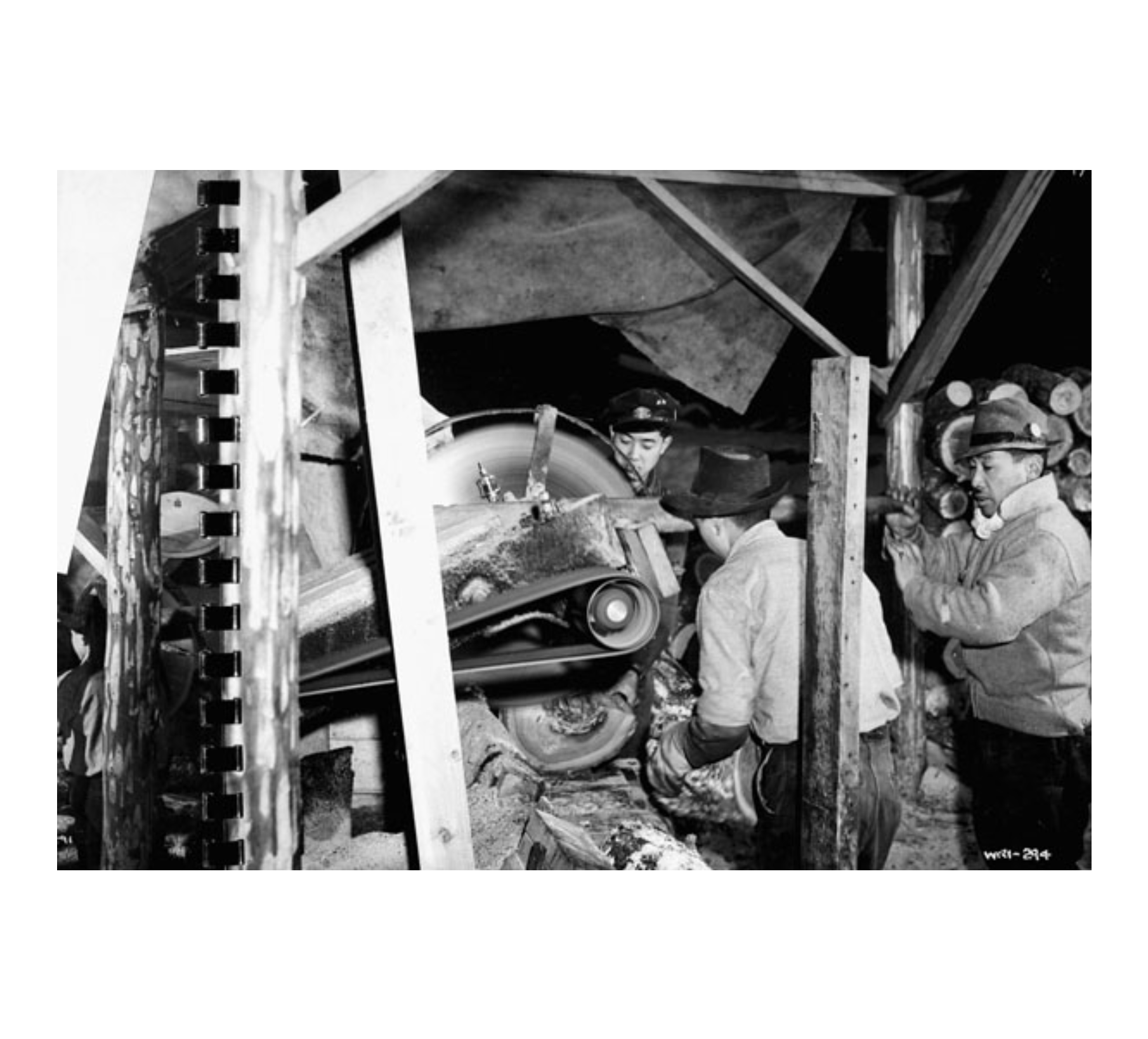

Interned Japanese Canadian men working at a sawmill in B.C., circa 1943. Photographer: Jack Long. Reprinted courtesy of Library and Archives Canada, Item ID 3379232

M: To that point, Professor Barrington Walker has argued that understanding the racist violence in Canada’s past is “not about digging up unpleasant stories about Canada, it’s about challenging a certain notion of historical innocence.” I think this has been a very disillusioning 12 months for a lot of Canadians who had a certain notion about what their country was and what it wasn’t. What can we gain from looking back at our history including the shameful and violent chapters?

TW: What’s prevalent for me is the depth of the racism that happened here. I mean, we look at what happened to Indigenous children. It’s completely unacceptable. I don’t have the words to express it. But if we know about it, we can prevent it from happening again.

And, we have to deal with the depth of the racism in this country. We cannot fool ourselves into thinking that we were in a very egalitarian country and that everything was rosy and that our history was wonderful. If we do that, then future injustice will take place. I think that there are a lot of lessons from the past 150 years that really do inform why we are where we are right now.

M: What comes next for you?

TW: I’m building my reputation. With the new novel, I would like to be able to address groups, do more interviews, to be a spokesperson for issues of racism, and to continue creating. I find it not only exciting and satisfying, but necessary to my being, and if I could stay relevant, that would be good.

I have no grand plans for the next novel, the next poetry book, the next play or whatever. But I’d like to continue and I hope I can.

To learn more about Terry Watada’s work, please visit the links at the top of this piece.

For more information on the internment of Japanese Canadians:

- visit the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre, who have uploaded many of their exhibitions for online visitors to explore;

- read Ann Gomer Sunahara’s The Politics of Racism, available to read online;

- listen to Terry Watada’s two-part documentary, Wasteland Gardens, which shares the experiences of three generations impacted by internment;

- and to learn more about the use of Hastings Park as a detainment site for Japanese Canadian women, children and tuberculosis patients, visit the Hastings Park 1942 website.

An important note about accessing photographs of internment camps through Library and Archives Canada: The Monitor is grateful for the important work that Library and Archives Canada continues to do to preserve the photographs, articles and other media that help preserve Canada’s history. However, it is important to note that the history that the Archive maintains is the official history, and not one that is rooted in justice or equity. Many of the photographs from Japanese internment camps still uncritically bear captions proclaiming the appropriateness of the decision to intern citizens, and the decency of the accommodations. By not addressing and adjusting this official record, the Archive risks creating ambivalence towards an event that was deeply harmful, rooted in racism and without justification.

Thank you to Lisa Ayuso and Gail Vanstone for their help arranging this interview.