It won’t surprise anybody that reads OS/OS that the costs of a university education is increasingly being transferred from governments on to the backs of students. Increasing tuition, government funding cuts and higher student debt have been the sad constant of Canada’s universities for decades.

Certainly, Saskatchewan has not fared much better than the rest of the country in this respect. While Saskatchewan has not declined as quickly as other provinces, it has nevertheless seen its proportion of funding from government fall from 54 to 50 per cent over the past 10 years. More troubling, over the past two decades real per-student spending has declined by 12 per cent in Saskatchewan, with only Ontario and PEI experiencing larger declines. In comparison, per-student government spending nationally has declined by only 3.4 per cent since 2001.

As government funding shrinks, universities have been forced to rely more on tuition fees, with international student fees fast becoming the go-to option to replace revenue lost to government cuts. Once again, Saskatchewan has not been immune to this trend, with universities seeing their proportion of funding from tuition and fees grow from 14 per cent in 2010 to 22 per cent in 2020. Similarly, Saskatchewan universities have also experienced increased reliance on international tuition with the proportion of tuition revenue from international students at the province’s two universities growing from just under 10 per cent in 2007 to 25 per cent in 2020.

As that reliance on fees has grown, so have tuition fees themselves. Saskatchewan’s current tuition fees for a domestic undergraduate program of $ 9,232 are second only to Nova Scotia, and over $2,000 more than the national average. While international undergraduate tuition in the province remains below the national average, it has increased by 67 per cent over the last decade, coming in at over $27,000 this year.

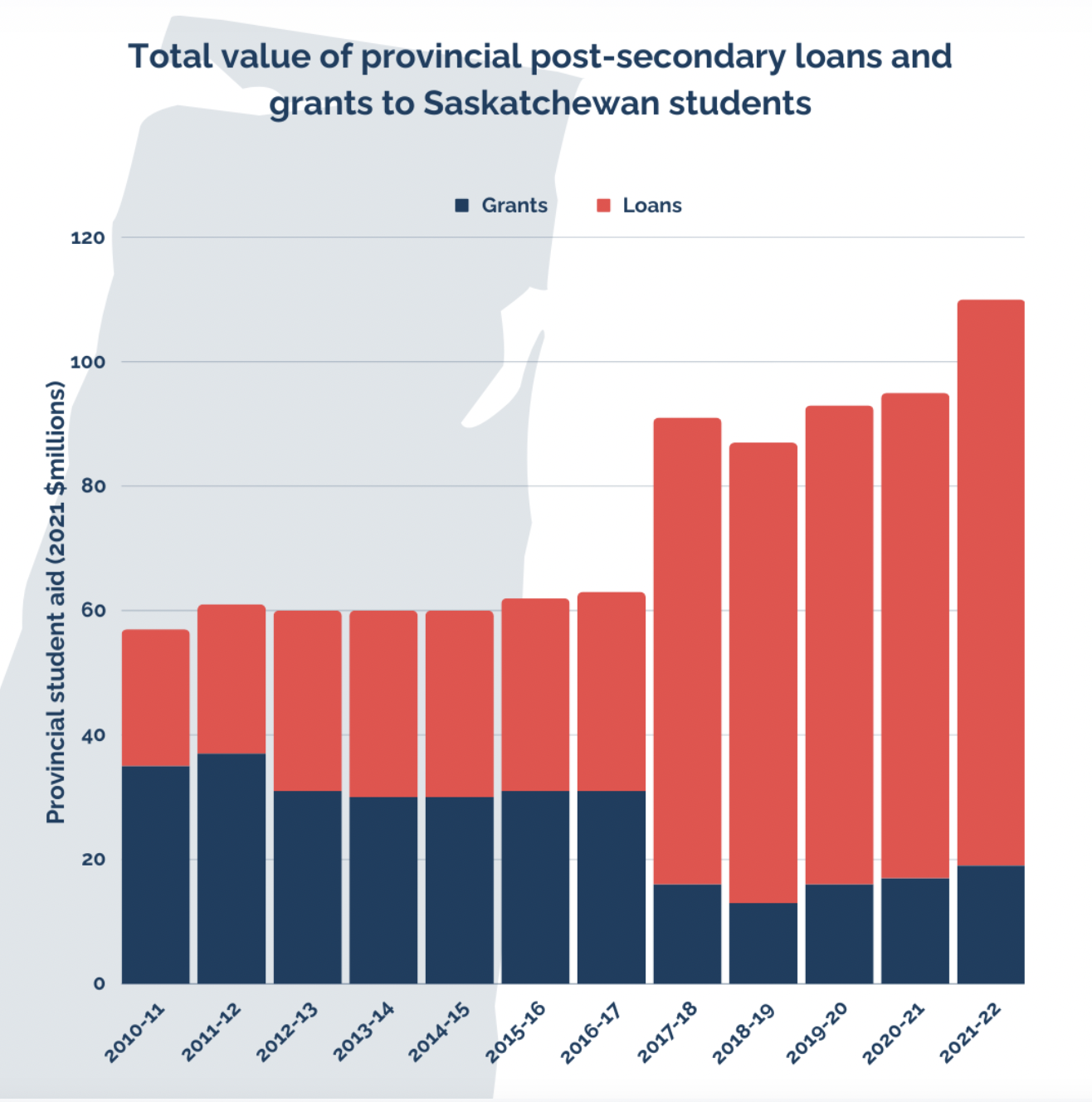

As you would imagine, this combination of declining government support and rising tuition fees has led students to depend more on loans to fund their education. Unfortunately, the government made significant cuts to Saskatchewan’s student grant system in their 2017 budget, forcing students to rely even more on borrowing rather than grants and bursaries. Indeed, as the graph illustrates, the student loan portion of student aid in SK exploded after 2017, while the provision of non-repayable- grants has cratered.

While we recognize the modern university requires a host of services and supports, it is curious that increased costs don’t appear to be going to the people that most of us associate a university with – academics. The proportion of university spending on academic salaries in Saskatchewan has declined from 37.5 per cent in 2000-01 to 30.9 per cent by 2020-21. In comparison to the national average, where academic salaries still outpace non-academic salaries, Saskatchewan has seen spending on academic salaries drop below that of non-academic salaries over the past five years. In 2020/21, universities in Saskatchewan spent the largest proportion of their budget (65 per cent) on items other than academic salaries and student aid of all the provinces.

Students are paying more, and taking on more debt, in order to support a university system that appears to dedicate less and less to the primary mission of the university – an academic education.

While we would like to think that governments would want to halt and even reverse these trends, the ‘solution’ that most conservative-minded provincial governments are embracing will only cause more damage. Governments in Ontario, Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan have become increasingly enamoured with U.S.-style “performance-based funding” (PBF) – which distributes monies for universities based on their ability to meet certain metrics such as graduation rates. To the average person, this can seem quite reasonable. Why not incentivize our universities to produce what appear to be positive outcomes? But if universities are financially incentivized to meet such metrics, then they will likely prioritize those goals above all others.

So, while maximizing graduation rates may seem like a good idea, the effect may be for universities to become more exclusionary, accepting only those students who have a high probability of graduating, while rejecting those (historically marginalized and under-represented groups) who do not. Certainly, this has been the evidence from the U.S., where a comprehensive review of PBF policies found there is “compelling evidence that PBF policies lead to unintended outcomes related to restricting access, gaming of the PBF system, and disadvantages for under-served student groups.”

Moreover, PBF systems invariably require extensive and costly administration to compile, monitor, report – and ultimately game – the new metrics. As University of Regina Education Professor Dr. Marc Spooner concludes, “It is no surprise that these frameworks have led to drastic deformations and growing bureaucratic bloat, while diverting larger and larger pieces of the pie away from teaching, research, and service—the very budget line items that best serve students and society.”

While governments like to cloak PBF in high-minded rhetoric about “accountability,” it may just be the newest way to disguise funding cuts from the public. Research from Saskatchewan’s own Ministry of Advanced Education into Tennessee’s PBF model concludes that “there has been a significant reduction in annual state appropriations to higher education institutions, and an increase in annual tuition and mandatory fees for students during the period that performance-based funding has been used.” Citing the overall impact of PBF in Tennessee, the Ministry observes that under that model, state appropriations for Post-Secondary Education have decreased by close to 40 per cent, while student’ share of funding for PSE has increased by 70 per cent.

PBF allows governments to transfer even more of the financial burden of a university education onto the backs of students, while allowing governments to wash their hands of any responsibility through the handy justification that the universities just couldn’t meet their metrics.

In every respect, PBF fails to reverse the troubling trends outlined above. It is certainly not the way forward for Saskatchewan. Only a real commitment to fund the future of our universities through reinvestment in the people and resources required to provide a quality university education can restore the promise of our public universities.

This article is based on the CCPA Saskatchewan report Fund the Future: The State of Saskatchewan’s Universities released in September.