How to deal with inflation is often reduced to a simplistic choice: do we increase interest rates or don’t we? But that ignores the fact that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) we use to measure inflation consists of a specific basket of goods, some of whose prices are directly controlled, or at least strongly influenced, by governments. This provides another route to controlling inflation: governments can lower or restrict the growth of prices of items that play a big part in the CPI, thereby reducing the average change in prices.

As I’ve said in a previous post, the high inflation we’ve seen this fall isn’t very broad based. Instead, only four out of about 200 price categories are driving inflation well above 2%—gasoline, house prices, new cars and meat—none of which have anything to do with government pandemic supports for businesses or the jobless. In any event, the jobless supports have now wrapped up (although business supports continue in a reduced form).

Driving these big price increases are high international oil prices, out of control speculation in real estate, a microchip shortage for new cars, and the price of animal feed combined with corporate concentration of meat processing capacity. Three of those four trends governments have little control over, but the fourth—big jumps in home prices—governments have a lot of control over (or could, if they wanted to).

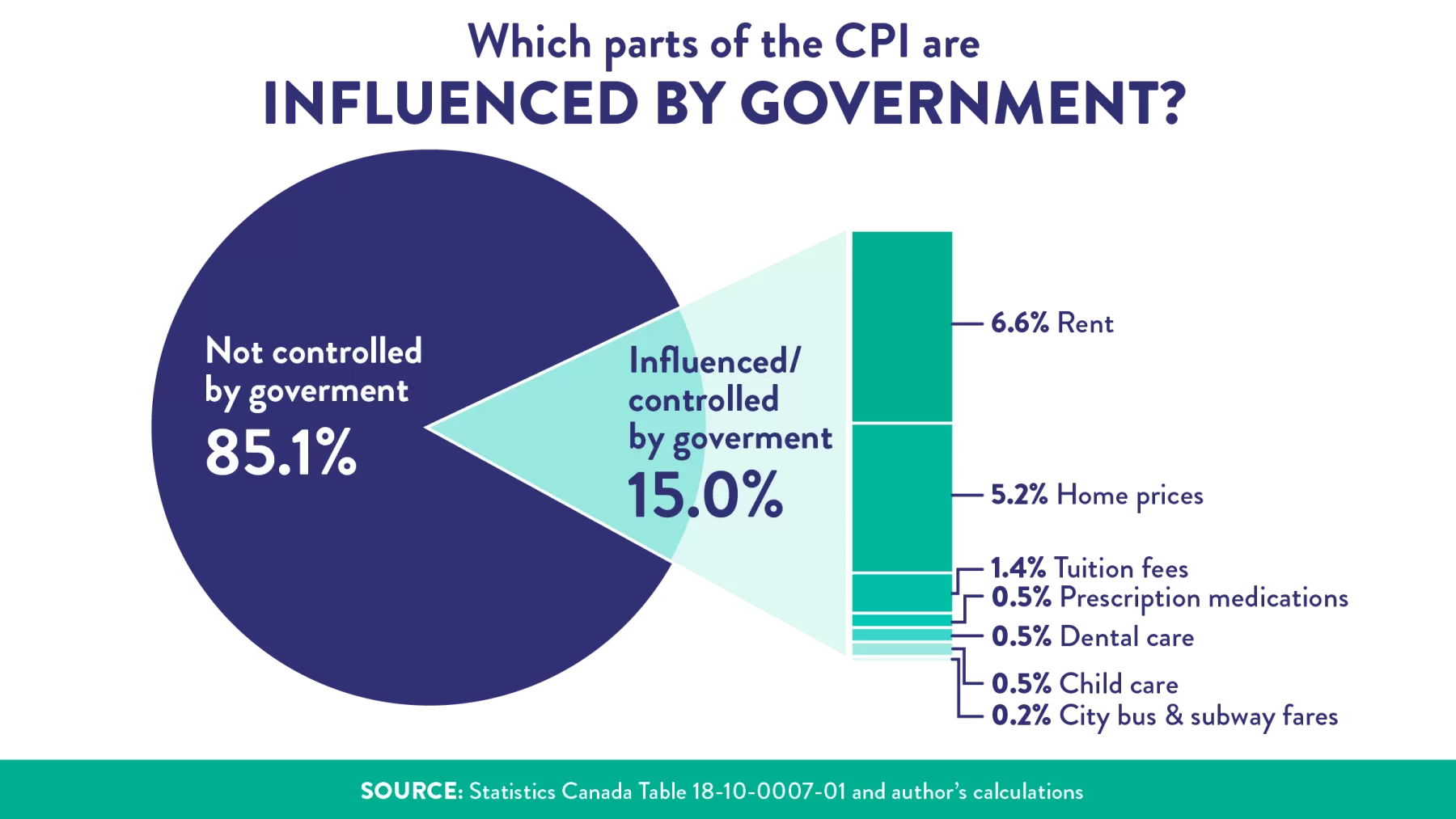

But how many of the other prices that make up the CPI are heavily influenced or controlled by the government?

The CPI tracks the prices of a specific basket of goods and services. Each item in that basket has a weight that represents how much an “average” household spends of their annual budget on that good or service. Because this is an average across all households, even though many households don’t have children and therefore aren’t buying children’s shoes, “Children’s footwear (excluding athletic)” still makes up 0.06% of the CPI basket.

The CPI weights change over time as Canadians’ buying behaviours change. For instance, “Internet Access Services,” which are in almost every household budget, make up a larger part of the CPI basket today compared to 2000 when they were much less common. As people buy less of something, possibly due to its higher price, that could also reduce the CPI weight. But the weights change slowly: the most recent change was in June 2021 which updated purchasing pattern weights to 2020 values. Prior to June 2021, the weights were from 2017.

Prices that are directly controlled or heavily influenced by governments represent one sixth of the entire CPI basket. This means if governments choose to reduce the prices in these areas, or restrict their growth, it could have a noticeable impact on the CPI. While it wouldn’t reduce the price of gasoline, it could offset that increase with reduced prices elsewhere.

The price with the largest weight under fairly direct control of governments is rent, making up 6.6% of the entire CPI basket. Already six out of 13 provinces and territories restrict rental increases for existing tenants. Two out of 13 restrict rental increases on units even between tenants. And in all provinces and territories rent can only be increased once every 12 months. While the maximum rental increase is generally set close to CPI, it doesn’t have to be. During the pandemic, several provinces had a rent freeze. Alberta is the only big province that doesn’t govern rental increases for existing tenants, but it could. Continuing with rent freezes is an easy way for government policy to limit inflation.

The second largest weight in the CPI—5.2%—where governments have plenty of influence is home prices (as the CPI is an average across all households, including those that own and those that rent, both home prices and rent are included in the basket). Unlike rent, governments don’t regulate how quickly house prices go up, but both federal and provincial governments have plenty of tools that could directly impact house prices.

The most significant is the availability of mortgage credit which can be influenced through mortgage stress tests to qualify for a mortgage or through conditions on mortgage insurance from CMHC. Particularly at the provincial level, there have already been increased taxes on homes in the form of vacancy and foreign buyers’ taxes. There is also the massive federal exemption from capital gains for principal residences. It’s well within the power of federal and provincial governments to push back against house price increases. This was a popular election promise, but it would also help to pull CPI back down to more normal levels.

The third largest government influenced price is post-secondary tuition, representing 1.4% of the CPI basket. In many cases, provincial governments have enormous influence on setting tuition fees through systems of grants or transfers to institutions. Directly reducing tuition fees would not only allow more students access to PSE but it could also bring down inflation.

The pandemic has revealed governments can and do have the flexibility to think differently about economics, and their approach to inflation should be no exception.

Prescribed medicines (the fourth largest area, representing 0.5% of the CPI basket), and dental care (making up an additional 0.5%) are both curious exceptions to health care coverage in Canada. Health care costs are generally covered by provincial medicare and don’t contribute to CPI at all. If you’re in a hospital, drug costs or dental surgery are covered; outside of one, medicare washes its hands of the matter. The most common childhood surgery is for cavities. Some provinces, like Quebec, already have limited forms of pharmacare which covers the cost of prescription drugs outside of hospitals. Several provinces cover dental care for children, and all provinces cover it for those receiving Social Assistance (See table 2). A national pharmacare program could yield large savings to Canadians; in addition, further extending dental care coverage, particularly for children, would cut parental costs and keep children out of hospitals. And in addition to these significant benefits, they would pull down the CPI too.

While a massive expense for parents of young children (over $20,000 a year for infants in Toronto), child care fees represent a modest 0.5% of the CPI. Provinces like Quebec have much lower fees because the province directly regulates them. The new federal plan to reduce child care fees for non-school aged children will absolutely pull down that portion of the CPI—even more so if Ontario finally signs on.

A final category is transit fees which are set directly by municipal governments who run those services. How much transit users pay is a political decision of local councils. Some, Ottawa for instance, have provided entire months free to transit users during the pandemic. Actually reducing transit fees (with possible provincial or federal support) could be great for the environment, not to mention driving down CPI.

Because governments have the ability to control or strongly influence key prices, they could use this authority to make life more affordable, reining in inflation at the same time. While it wouldn’t decrease the price of gas, it could offset it through lower tuition fees, cheaper child care or transit, or a rent freeze.

Economic textbooks often describe inflation as a general phenomenon abstracted from actual prices, but in actuality the CPI is built up from prices people pay for various goods and services every day. The pandemic has revealed governments can and do have the flexibility to think differently about economics, and their approach to inflation should be no exception. Tackling inflation can be part of a public-led recovery—it only requires governments to use the tools at their disposal in key areas that are driving inflation. There is no time to waste—otherwise the more orthodox approach of raising interest rates to quell inflation will be the order of the day.