With the reopening of the economy in June, more women are back at work and others are picking up more hours, but their recovery continues to lag that of men. This unequal situation creates numerous challenges for Canada as we move into what may be a long, slow recovery, especially in female-dominant sectors of the economy.

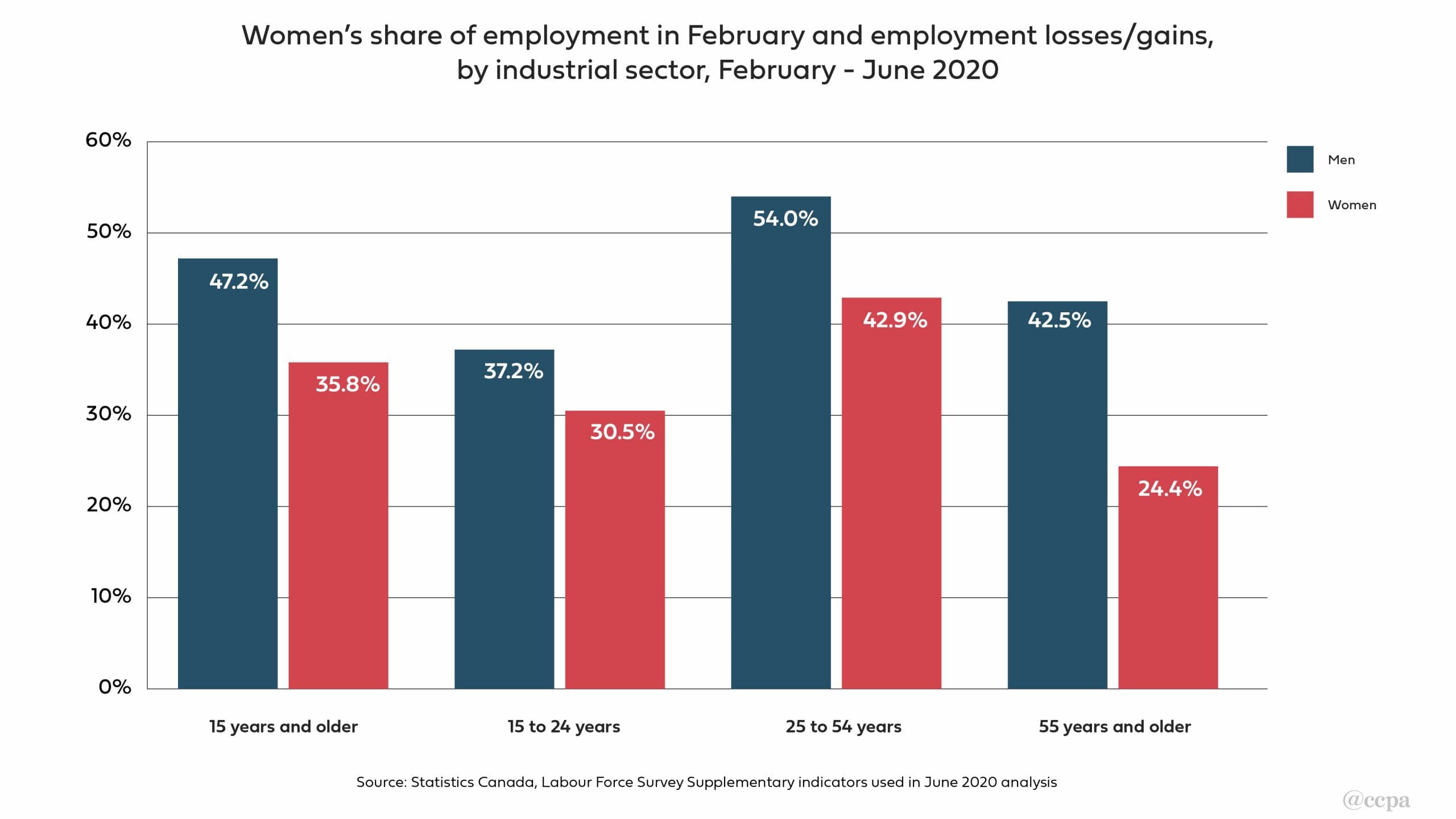

The June jobs report from Statistics Canada shows that, since April, women have recouped one-third of February-April employment losses (35.8%), the equivalent of about 550,000 jobs. Core-aged women (25–54) saw larger gains than youth (15–24) and older women (55+). For all age groups, the recovery among men is more advanced.

While these gains are important and provide hope for long-term recovery, the number of the unemployed and underemployed is still significant. In June, 2.5 million people were out of work (1.3 million above the levels posted in February) and another 2.2 million were working less than half of their regular hours. Women continue to account for more than half of all losses (53%).

Another large group of women left the labour force through the first months of the pandemic and have yet to return. Among core-age workers, the proportion of women “not in the labour force” was down from a high of 22.2% in April but is still 8.3 percentage points higher than in February. Not everyone is finding their way back.

With no child care, no recovery for women

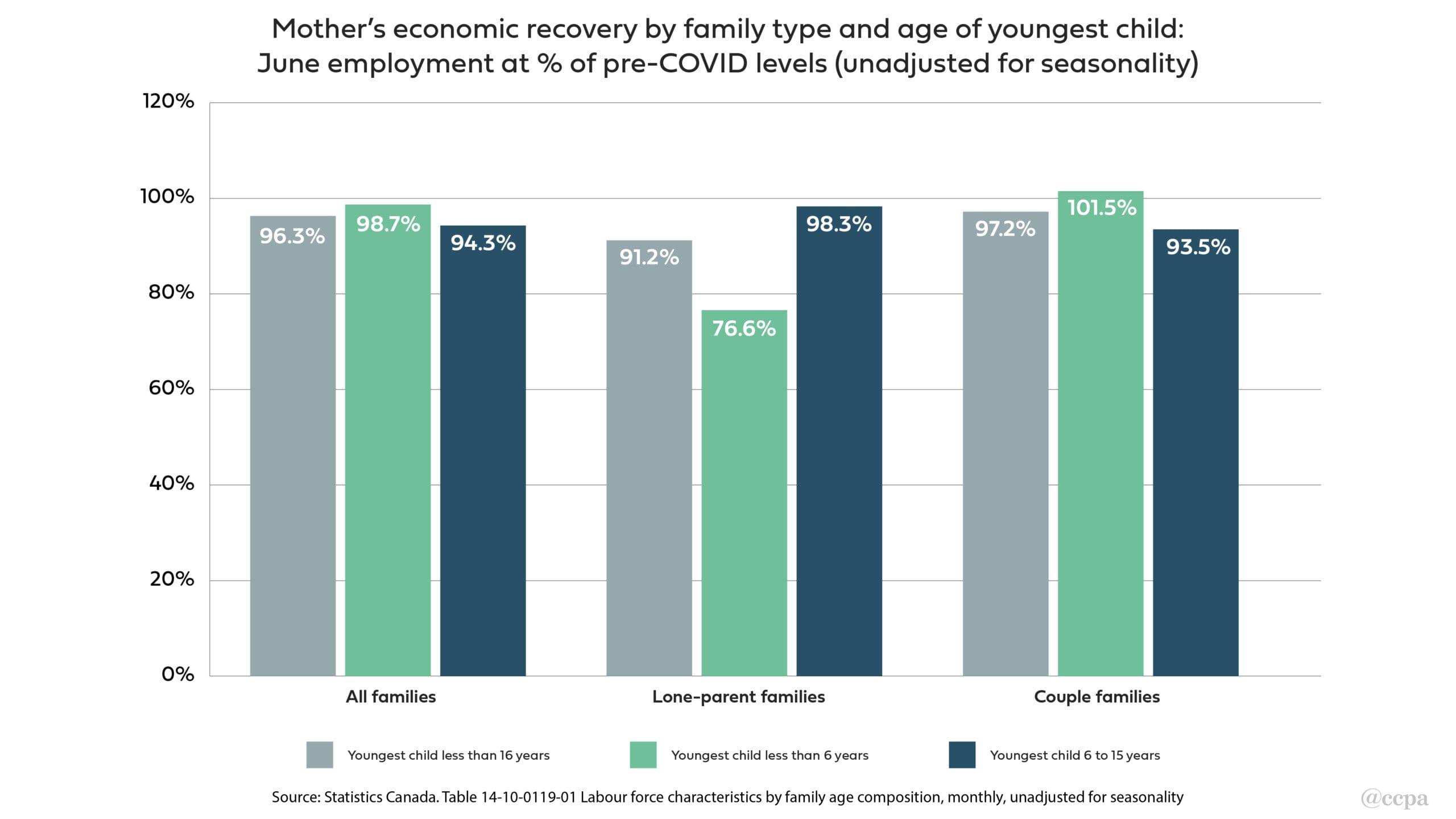

The lack of a coherent or safe plan to reopen child cares and schools creates significant barriers for women, particularly mothers, wanting to re-enter the workforce. Social norms and the traditional caregiving roles of women, which have contributed to gender gaps in pay, are now pushing mothers, rather than fathers, out of the labour market and into full-time caregiving and homeschooling.The gains in employment have clearly been weaker among mothers with children under 16.

Lone-parent mothers with kids under six had only recouped 19.6% of their February-April employment losses by mid-June. Rates of employment among mothers with school-aged kids living in couple families were also still significantly lower than in February (figures not seasonally adjusted).

Mikal Skuterud of the University of Waterloo provides additional evidence of the constraints mothers are experiencing in his analysis of aggregate hours worked since February. Women whose youngest child was aged six to 12 had recovered only 36% of their lost hours by mid-June, while mothers of young adults aged 18 to 24 were 78% of the way back. The challenge was especially acute for lone-parent mothers who had only recovered 23% of their hours by June.

An unequal recovery is unfolding

June’s jobs report also highlighted again “the brutally unfair concentration of this recession,” as Jim Stanford describes it, “on the backs of those who can least afford it.”

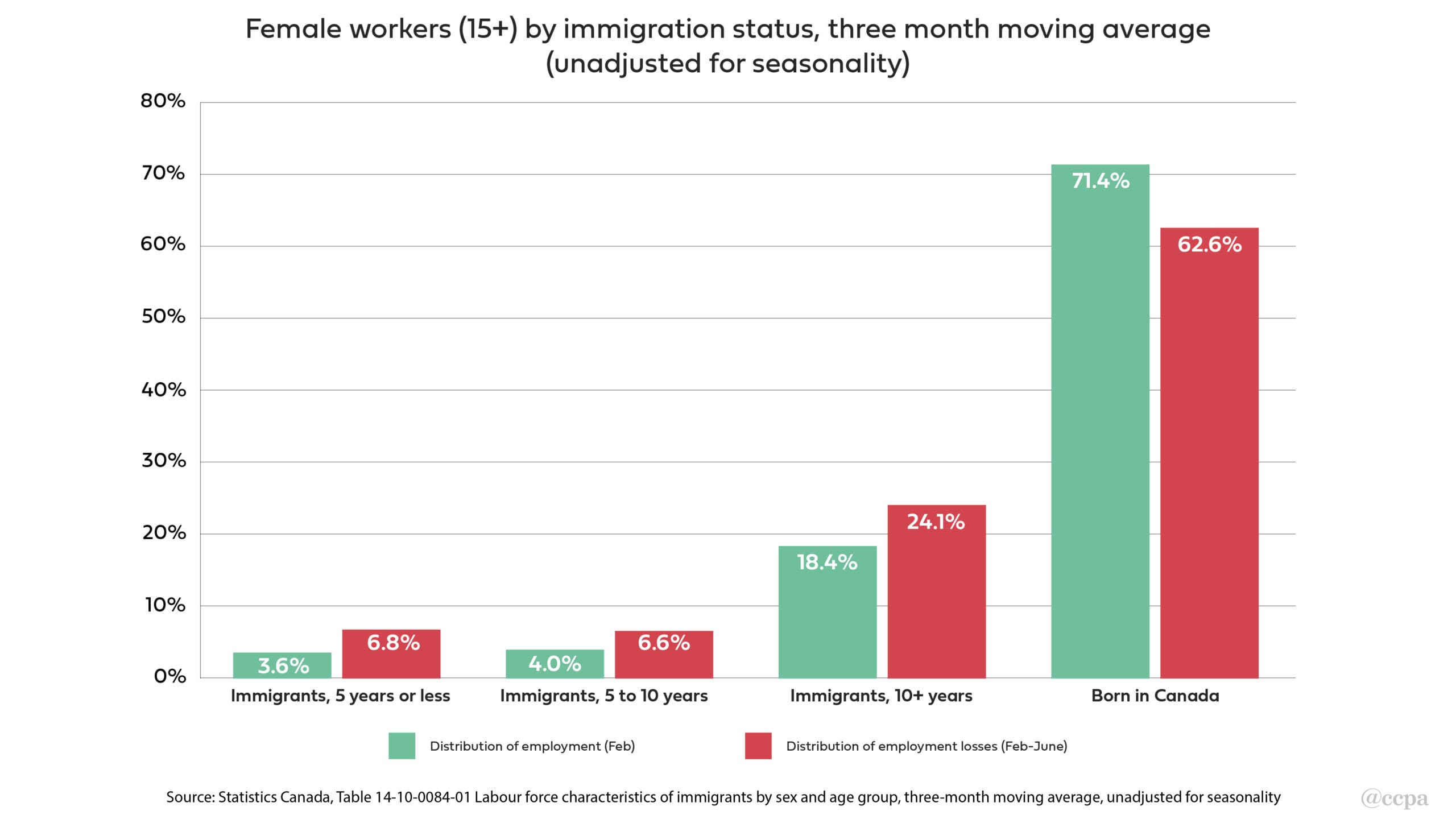

Women, young workers, workers in temporary and precarious jobs, immigrants and migrant workers have all experienced disproportionate harm from the crisis, particularly those facing intersecting forms of discrimination.The rate of recovery among low-wage female employees, for instance, lags that of low-wage male employees by 10 percentage points (74.8% vs. 84.7%).

The recovery of all low-wage employees, in turn, lags that of workers earning higher wages (78.8% vs. 96.7%).Likewise, temporary female workers are only 82% of the way back to February levels, recouping only 42% of losses recorded between February and April. Permanent female workers, by contrast, have reached 92% of their February employment levels, recouping 51% of losses (figures not seasonally adjusted).

Many temporary workers are immigrant and racialized women concentrated in sectors such as retail, food and accommodation, health care and social assistance. Immigrant women represented one-quarter of all female workers over 15 (26.1%) in February, but over one-third of employment losses (37.4%) by mid-June.

The situation in female-dominant industries

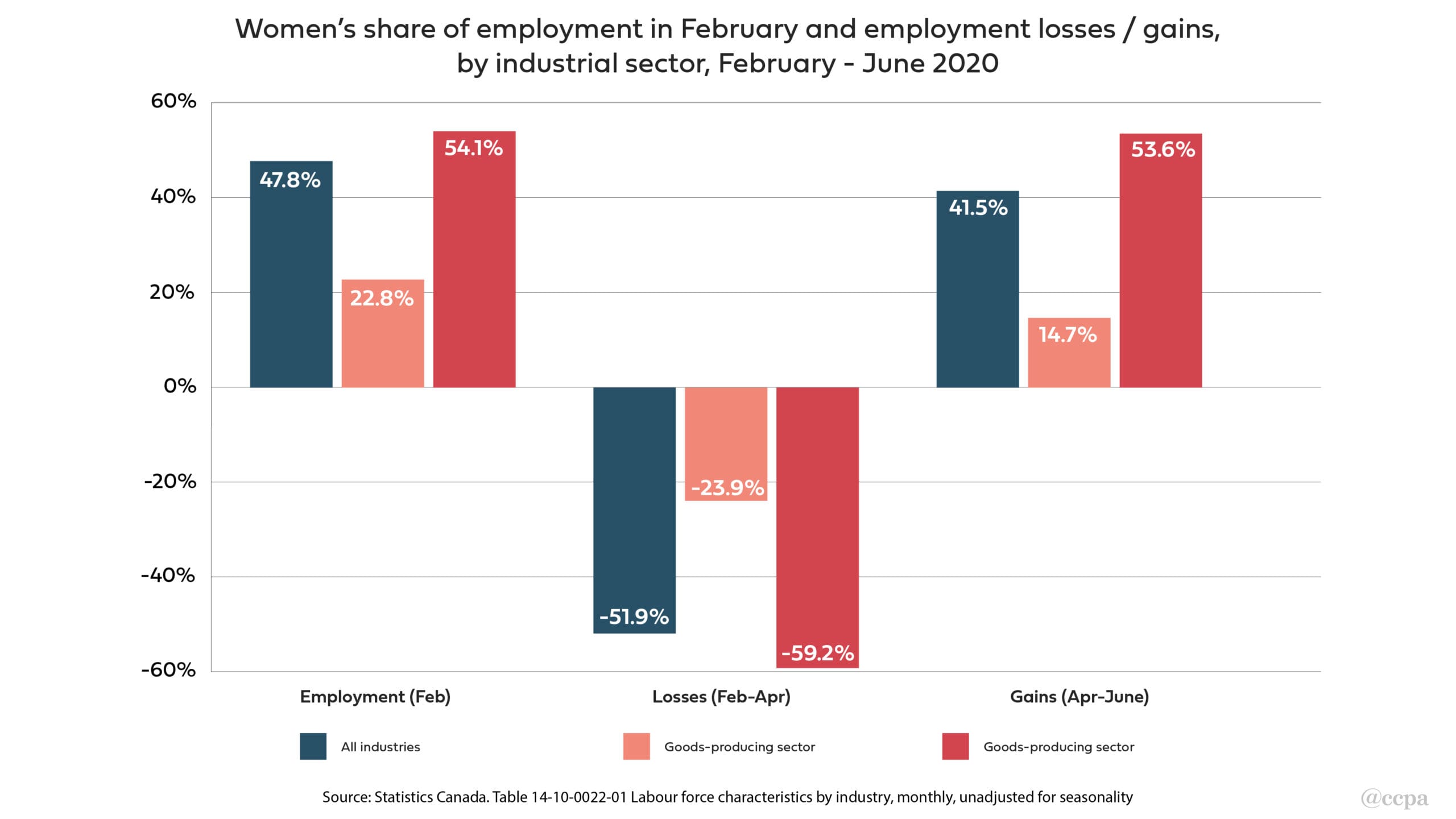

As predicted, the service sector is rebounding more slowly, notably among industries and occupations where workers are in close physical proximity with each other. With the easing of restrictions, there has been a sizable boost in employment, but rates remain well below February levels.

In an industry such as financial services and real estate, women represented 51.0% of workers in February but accounted for more than half of losses (-60.3%) between February and April and an even smaller share of employment gains between April and June (+23.6%). The distribution of losses and gains in retail was more balanced between male and female workers, but consumer demand remains low and many businesses are shuttered. Women in retail had only recouped 39.8% of employment losses by mid-June.

In female-dominant industries such as health care and social assistance and educational services, women account for the majority of employment losses and then the majority of gains. Overall, the scale of employment losses in these industries has been more modest as women have continued to work in essential jobs throughout.

Others in professional jobs within these sectors have been able to work from home, but families with children among them face the daunting task of juggling care and schooling. Years of schooling will not protect women against the collapse of Canada’s fragile and porous child care system.

A feminist recovery plan

The widening employment gap between women and men represents a huge threat to women’s economic security and that of their families. Prior to the pandemic, women earned 42% of household income and were, on average, responsible for almost half of household spending. The precipitous collapse in employment will inevitably lead to greater financial hardship, not just in the coming months but for years to come.

RBC Financial estimates that, absent a second wave of the virus (a big if), employment will recover to within 2.5 percentage points of pre-COVID-19 levels by the fourth quarter of 2020. But the extent of the recovery will vary hugely from industry to industry. Employment in accommodation and food services, where women dominate, may take years to recover (an example of a devastating “L” shaped recovery), whereas male-dominated manufacturing, construction and natural resources are already springing back (following the much more desirable “V” shaped path).

What is certain is that, without focusing recovery efforts on the needs of those experiencing the greatest barriers, progress towards greater gender equality will be rolled back decades and the recovery itself will be prolonged, with hugely damaging consequences for the whole society.

The loss of employment is about so much more than economic autonomy. It is about freedom from violence and poverty, about the ability to improve your quality of life, and about your capacity to avoid risks. It’s about the capacity for all of us to thrive.

Strong voices are needed to advance a feminist recovery plan in the face of entrenched privilege, institutional lassitude and interminable federal-provincial wrangling. One week we have an “Economic and Fiscal Snapshot” from the federal government that acknowledges the gendered impact of the crisis.

The next, an announcement of $19 billion to assist provinces and territories restart their economies, only 3% of which is set aside for child care, 2.5% for those experiencing challenges related to mental health and homelessness, and perhaps 4% for long term care.

Willful negligence, callous disdain. Take your pick.

A gender-just recovery demands an approach that centres the needs and perspectives of women, girls and gender-diverse people. We must continue to fight for a feminist recovery plan. This is our chance to bend the curve of public policy toward justice, well-being and sustainability.

Katherine Scott is a Senior Economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Follow her on Twitter @ScottKatherineJ.