We are far less likely to recognize households living in poverty as a public health issue, societal crisis or economic problem that we should solve collectively.

We are far more likely to think that it should be dealt with by charity or that they should ‘pull themselves up by their own bootstraps.’

Government revenue allocated for health, education and other public services or income supports is never quite framed in the same way as infrastructure spending—rarely is it presented as necessary investments in the health and well-being of our population.

Rather, for the past few decades, the spotlight on provincial budget days has focused on lowering government debt through restriction of spending on public services.

Focusing on our fiscal deficits, and not enough on our social and economic deficits, has a cost.

The purpose of the report we just released is to illustrate the shared economic cost of poverty, and the urgency that exists for Atlantic Canadian governments to act to eradicate it.

The collective decision not to address poverty in our communities affects our ability to reach our full potential—because members of our community are being held back.

Even though provincial governments claim to be focusing on decreasing public debt in the name of lessening the burden for future generations, the next generation’s families are still taking on this debt privately, as household debt.

Families struggle to pay the high costs associated with child care, tuition and prescription drugs, because our governments have not done enough to expand public services or make essential services accessible and affordable, such as housing, electricity, cellphone and internet services.

Communities, municipalities, charities and non-profits, have also been trying to fill the gaps left by governments’ underinvestment in income supports, as well as public services and programs.

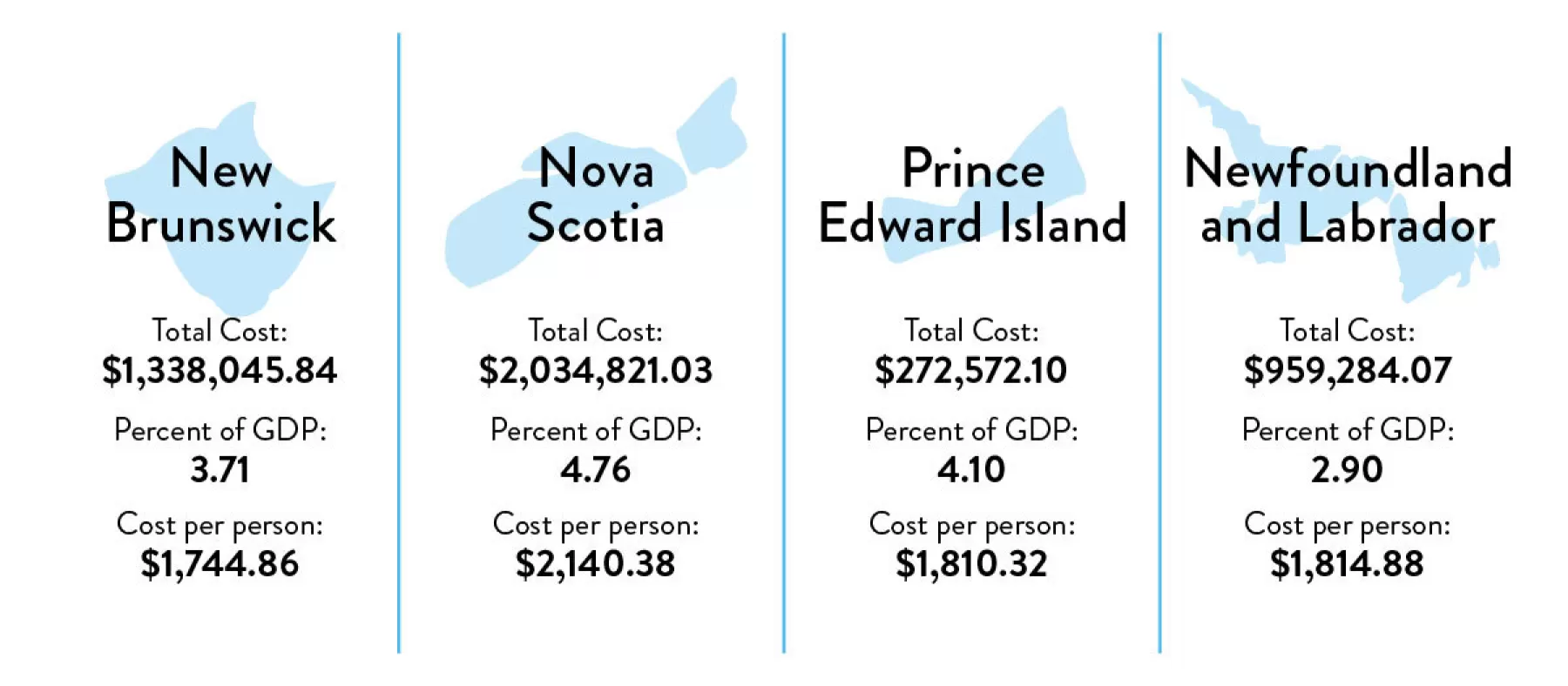

Not addressing the needs of the population costs provincial governments, too. The cost totals $2 billion per year in Nova Scotia, $1.4 billion in New Brunswick, $273 million in Prince Edward Island, and $959 million in Newfoundland and Labrador.

These costs represent a significant loss of economic growth: 4.76% of Nova Scotia’s GDP, 4.10% of Prince Edward Island’s GDP, 3.71% in New Brunswick and 2.9% in Newfoundland and Labrador.

As the Atlantic provinces consider how to support the region to recover from the pandemic, eradicating poverty must be an important part of that recovery plan. Doing so also enables us to build stronger, more inclusive provinces.

The collective decision not to address poverty in our communities affects our ability to reach our full potential—because members of our community are being held back.

This cost of poverty exercise considers what the gains would be if we were to raise the standard of living for those in poverty. Given that poverty is racialized and gendered, and that certain groups have been made more vulnerable to living in poverty, eradicating it is part of addressing income inequality and social inequities in our society.

These monetary costs cannot fully capture the toll that poverty takes on people’s health and well-being, on parents who aren’t able to provide for their children’s needs, on children who go to school hungry, on those who are without homes, unable to afford healthy food and the basic necessities.

The impact that the stress of living in poverty has on people’s lives—their physical and mental health, their relationships and their ability to be included as equal members of our society— shapes their lives.

The Atlantic provincial governments and the federal government have an obligation to end poverty.

To do so will require a comprehensive approach that provides adequate income supports and services, investments in programs and public services, as well as policy changes to ensure that everyone has access to what they need to reach their full potential.

As the UN Declaration of Human Rights says: “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.”

We should not have to put a price tag on what is a basic human right.