Key points:

- At least 1.17 million post secondary education (PSE) students or recent grads will use the Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB). They wouldn’t have been able to access the CERB.

- 620,000 PSE students will receive the more generous Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) instead.

As the winter term winds down, students facing a brutal job market this summer have been waiting for promised relief. More than 44,500 have expressed concern on #Don’tForgetStudents petition. An open letter to Trudeau sent April 15 on behalf of dozens of Canadian student associations called on the federal government to make sure students did not fall between the cracks.

On April 23rd, the federal government finally took steps to fill some of these gaps. The new Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB) will provide $1,250 a month from May through August for current students, those starting in September, and recent graduates, and $1,750 to students with disabilities or those taking care of others.

Like the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), it will also allow students with monthly earnings of $1,000 or less to gain access. The CERB for (some) workers and the CESB for PSE students provide two very different approaches to massive job losses. The student benefit is much closer to a basic income. It will go to all students with few requirements besides broadly being a PSE student, becoming one, or having recently been one.

The tradeoff for this broader coverage is less money per person at only $1,250 a month, compared to the worker emergency response of $2,000 a month. However, that higher value comes at the cost of less access: 1.4 million jobless Canadians did not receive any income support in April. (That being said, even though it’s not as universal as the CESB, the CERB is still much more inclusive than the old EI system it replaced.)

Students who were working on March 15th and have earnings over the $5,000 threshold (for 2019 or the last 12 months) have access to CERB benefits.

Students making under $1,000 a month can also receive the CERB due to that modification on April 15th. You can only claim one emergency benefit or the other and, for those given the choice, people will claim the CERB as it pays more.

Student have been hit hard by the pandemic

The days of postsecondary students earning enough money in the summer to pay tuition and support themselves through the school year are long gone. There has been profound change over the decades as many more students are now working year round to make ends meet, pay the rent, supplement family income, and finance their education.

On this score, education costs have been rising rapidly, outstripping the cost of living in every province. Student debt figures tell the story.

On average, students are graduating with nearly $28,000 of total debt from government and private sources. In many provinces, financial assistance has actually declined and insolvencies among student debtors are on the rise. In Ontario last year, the government retroactively converted available grants for low income students into loans and eliminated the six month repayment grace period.

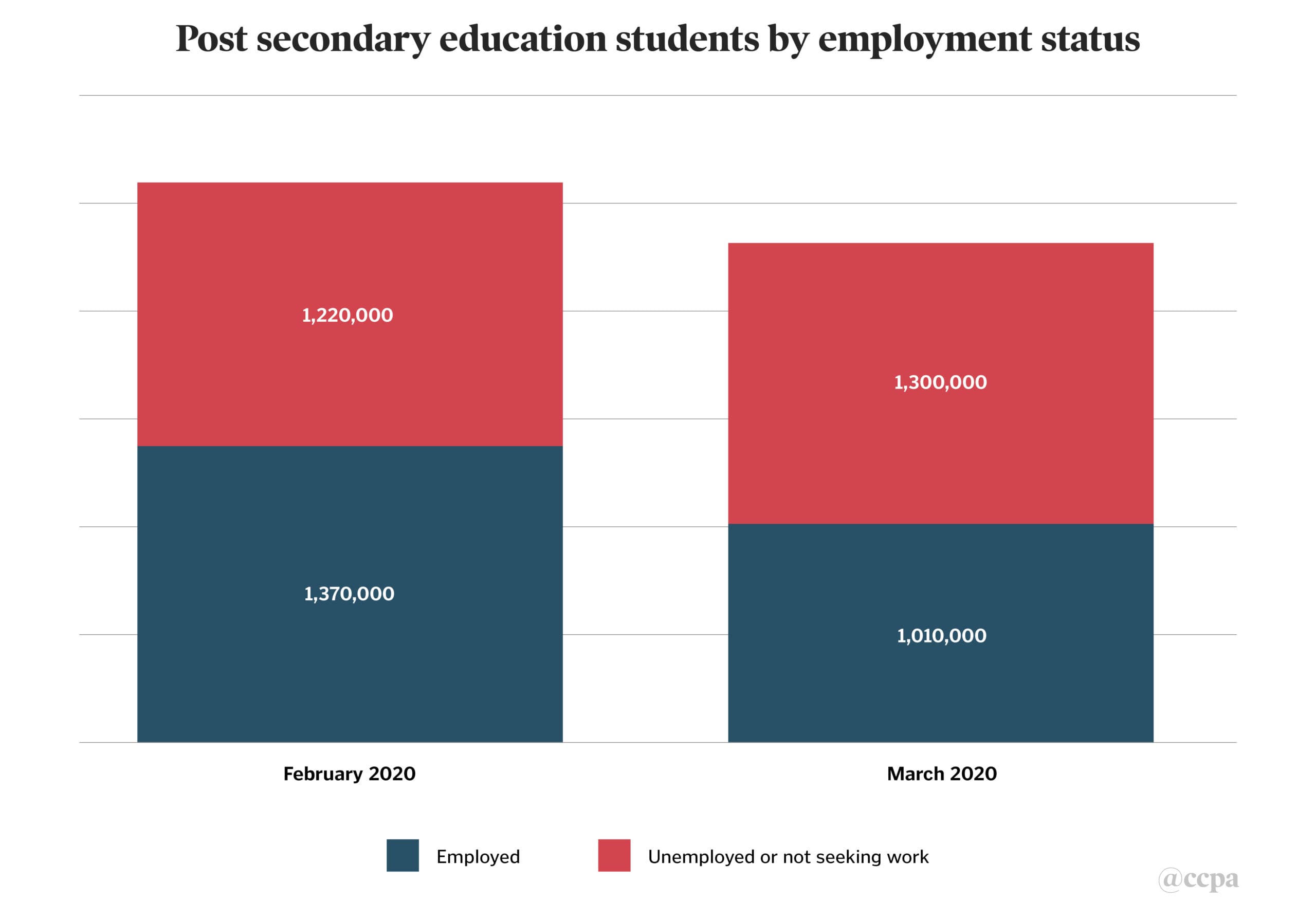

These actions weigh most heavily on students from marginalized communities—precisely those who are being hit hardest by the pandemic. In February, there were 2.6 million PSE students in Canada, 1.4 million of them were employed and 1.2 million of them were not. The total number of PSE students fell in March by 280,000 due to either graduation or dropouts. That left 1 million PSE students employed in March, although it actually includes 210,000 who had zero hours, so while technically “employed” they were making nothing.

The COVID-19 crisis hit students hard with almost 400,000 of them losing either their jobs or all of their hours (while remaining technically employed). Many, though not all, of this group, would be eligible for CERB (340,000) as they lost their jobs or weren’t earning anything. A portion (50,000) wouldn’t have the CERB requirement of $5,000 in employment earnings in the previous year.

Over and above the 190,000 PSE students who fully lost their jobs due to COVID-19, there were another 1.1 million students who, because they were unemployed or not seeking work in March, aren’t eligible for the CERB. The fate of the 280,000 PSE students in February who weren’t students in March is less clear. Some surely became unemployed and could receive CERB, but the exact number and how many would be eligible for which—if any—supports, is difficult to ascertain. Meanwhile, 800,000 PSE students continued to be employed in March; however, many of them aren’t making very much; 270,000 of those students make under $1,000 a month and therefore could get the $2,000 CERB top up while employed.

As the CESB seems to be essentially universal for anyone who can show they are, or are going to be, a PSE student or recent graduate, all of those students who couldn’t get CERB likely will be able to get the CESB. The definition of “PSE student or recent graduate” is forthcoming, and obviously the details matter; for instance, how long ago does one need to show they were a student or need to have graduated?

The table in this analysis starts the clock in February 2020, but it could clearly go further back, thus increasing the number of students covered. At the very least, there are 1.17 million students who aren’t employed and aren’t getting the CERB and would be eligible for the CESB. The additional 280,000 who were students in February but not March would almost certainly be eligible for the CESB, but it’s unclear how many would need to claim it. Their number would certainly increase the 1.17 million figure.

What happened to PSE students between February and March 2020?

Employers across the board are suspending job competitions and retracting job offers. Even as the economy gradually reopens, it is unlikely that public-facing jobs—jobs that typically employ large numbers of students—will be at the top of the list. Come May, many will be unable to meet their immediate needs. Not every student can fall back on their families for a place to stay or the funds to tide them over this crisis (however long that may take) as these families are struggling with the fallout from the pandemic as well. Summer is the prime earning season for students to help them defray the rising cost of tuition along with the general costs of getting by.

Typically between March and July the proportion of those aged 20 to 24 who are working jumps a full 10 points which, for this age group alone, would mean an additional 240,000 people seeking work (although they’re not all PSE students). As noted in the table above, 1.2 million PSE students will likely be eligible for CESB, a large portion of which would have been looking for a summer job. This analysis is further complicated with the planned end of the CERB by July, while the CESB is meant to run from May to August.

There is yet to be a clear transition plan from CERB back to EI. With the number of CERB recipients growing daily, it’s hard to see how that July transition could happen. Currently, 620,000 PSE students are at risk of being pushed from the more generous CERB to the less generous CESB when the CERB ends in July.

Other parts of the April 23rd student aid package

A new Canada Student Service Grant will provide up to $5,000 towards education for students who volunteer this summer with a new national service initiative, but the details remain fuzzy. Federal funding for the Canada Summer Jobs wage subsidy program and related youth programming has been expanded again and will now create up to 116,000 job placements for youth aged 15 to 30 years through to next February.

Additional funds will be directed to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Nation postsecondary students and to the granting councils to support graduate students through scholarships, fellowships, grants for RAs and TAs, etc. The value of Canada Student Grants will be doubled for full-time students (up to $6,000 for full-time students and $3,600 for part-time students in 2020-21), and eligibility for student aid through the Canada Student Loans Program will be expanded and maximum weekly amounts increased by 60% to $350 per week for full-time students.

The government estimates that the number of students accessing one or both of these programs will increase from 700,000 to 760,000 in the 2020-21 school year. Based on 2016-17 program figures, we can expect that a minimum of 250,000 low income students (roughly 10% of all students) will receive a maximum of $11,000 in grant funding to cover the summer and next school year. The rest will make do with less. Removing the expected student contribution requirement for those applying for student loans will significantly increase the amount that students are able to borrow to finance their educations. It also means that students will be taking on higher debt loads—and repayment challenges—down the road.

Taking out loans not only increases the overall cost of the degree, but it can financially impact students for years, affecting career choice and future income as well as the likelihood of owning a home or even saving for emergencies. The Canadian Federation of Students has also been calling attention to the plight of international students who make up 20% of the overall student body, many of whom desperately need assistance as well. International students who lose their employment as a result of the pandemic are able to apply for CERB, but others won’t be able to access the CESB.

Investing in students long term

The total value of this assistance package is $9 billion. In short order, the federal government has marshalled a considerable sum of money to directly support students. But the pandemic also represents a profound economic challenge for universities and colleges. Twenty-five years of reduced public support for postsecondary education—at both levels of governments—have left educational institutions hugely exposed. Universities used to receive more than 80% of their operating revenue from government. Today, government funding has shrunk to barely 50% and more than one-quarter now comes from tuition fees.

But will students be able to afford to attend? Will international students be able to come? The steepest drop-off in September enrolments at Canadian universities may well come from this group, who pay much higher fees than Canadian students. Getting money into the hands of students is probably the fastest way to stave off massive tuition fee hikes and lay-offs in the postsecondary sector. But what next? These programs have been brought in as one-off measures.

As the economic fallout persists, young people with limited labour market experience will face huge barriers both to education and employment, particularly students from marginalized communities. The new student aid package will provide some immediate relief. But this must be a down payment on a more transformative package that supports all students through the pandemic and enhances federal financing for the post-secondary sector with the goal of eliminating tuition fees, reducing institutions’ reliance on private and corporate funding, ending the dependence on precarious workers, and providing meaningful support for low income and marginalized students.

David Macdonald is a senior economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Follow him on Twitter at @DavidMacCdn. Katherine Scott is a Senior Economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Follow her on Twitter @ScottKatherineJ.