This summer marks the five-year anniversary of the Canadian Free Trade Agreement (CFTA), a provincial pact with the federal government that flies well below most people’s radars. Despite its young age, the agreement is looking like a dusty relic that’s out of place in today’s world.

In fact, the deal’s single-minded focus on eliminating so-called barriers to interprovincial trade—by harmonizing regulations, standards and occupational safety rules—creates its own barriers to better environmental policy, stronger worker protections, and the transition we need to a more sustainable and equal society.

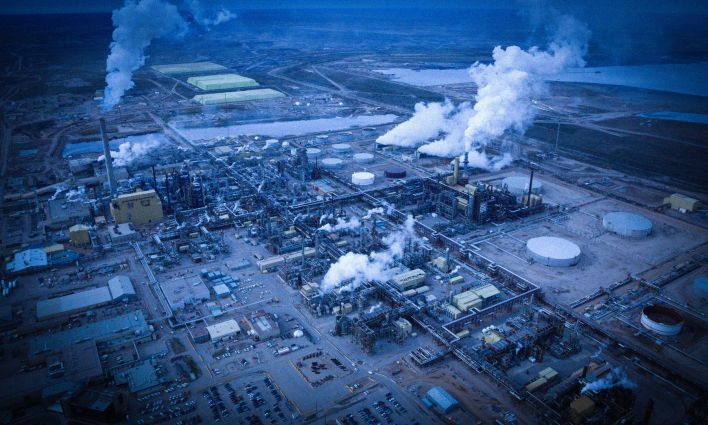

When the CFTA entered into force five years ago, the scale and urgency of responding to the climate crisis was already apparent. It took the COVID-19 crisis and aftermath to expose just how unprepared we are to meet a cascading set of related environmental, economic and public health breakdowns.

For example, Canada was ill-equipped to manufacture ample personal protective equipment, ventilators or vaccines when they were urgently needed. We failed to anticipate, and then respond to, the health risks and unmet care needs of our aging population.

We didn’t understand that corporate concentration and supply-chain vulnerabilities could trigger an inflation-ridden recovery and the sudden failure of critical infrastructure like our telecommunications network.

To face these intersecting challenges, we must expand both Canada’s domestic productive capacities and government’s policy imagination. Unfortunately, the CFTA, like Canada’s many international trade agreements, makes both feats unreasonably difficult.

The CFTA, like its precursor Agreement on Internal Trade, was drafted solely to “reduce and eliminate, to the extent possible, barriers to the free movement of persons, goods, services, and investments within Canada.” Climate change receives the barest mention. Women and gender equity are passed over in silence, and labour rights are accorded short shrift.

Most activity under the CFTA umbrella occurs at the Regulatory Reconciliation and Cooperation Table (RCT). The RCT, which includes senior provincial, territorial and federal officials, receives proposals from businesses or governments to eliminate “barriers or irritants” to commerce in the form of differing regulations or standards. If enough provinces agree, a “table” is established to try to reconcile those differences through either harmonization or mutual acceptance of provincial rules.

Climate change receives the barest mention. Women and gender equity are passed over in silence, and labour rights are accorded short shrift.

Sometimes the identified “barriers” to trade may seem small, like differences in what safety products must go into first aid kits in workplaces. Other RCT agenda items, like reconciling occupational exposure limits for certain toxic chemicals or the adoption of company-policed safety management systems (versus public oversight) in workplaces across Canada, could have far-reaching impacts.

We should be concerned that these important decisions about working conditions and product safety are being made with a view to reducing the burden on business—not primarily with a view to what would be best for workers, the environment or the public benefit. Why should industry have privileged access to an intergovernmental regulatory reform body with little transparency or accountability to civil society?

The CFTA approach to interprovincial cooperation is also profoundly inadequate to advance the society-wide economic transformation required of us.

The goal of strengthening Canada’s economic resilience doesn’t appear at all in the agreement. In fact, economic measures to incentivize or sustain local jobs and production are purposefully excluded from the CFTA’s definition of “legitimate” policy objectives—areas where governments may deviate from trade rules in limited circumstances.

To be sure, many provinces reserved some space in the CFTA to impose performance requirements on investments to create good jobs and stimulate local economies. Several provinces, including Ontario and New Brunswick, also have policies in place to favour local companies in government contracts where allowable under the CFTA’s strict procurement rules.

These are important steps. But instead of limited exceptions in otherwise highly restrictive free trade deals, we must rethink the economic and regulatory framework needed to put Canada on track to meeting its climate objectives and cushioning Canadians from future economic and public health shocks.

The transition to a net-zero emissions economy will be a herculean task for which market-based or trade-focused solutions are inadequate. As Seth Klein has persuasively argued, governments must relearn how to plan, coordinate and nurture investments in all areas of the green economy.

That will mean expanding domestic manufacturing. It will mean transforming our energy, agricultural and transportation systems. It will mean fostering public- and private-sector innovation in green technologies. It will mean using procurement strategically to support those technologies. And it will mean prioritizing skills training and workforce development.

The five-year anniversary of the CFTA is a chance for the federal, provincial and territorial governments to engage the public about the post-pandemic industrial strategy we need to meet the urgent challenges in front of us. If the trade agreement creates barriers to moving that agenda forward, those barriers should be removed.