This article is a translation of a piece that was originally published in French by the Institut de recherche et d’informations socioéconomiques (IRIS). Click here to read the original.

The remaining global carbon budget for limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius is 400 Gt. Yet, exploiting currently operating fossil infrastructure (wells, oil pipelines, refineries, etc.) to the end of its expected lifetime would be enough to exceed this threshold by more than a third. To counter the climate crisis, avoiding new fossil fuel installations is not enough: some existing infrastructure must be dismantled prematurely.

Several obstacles are delaying and preventing this transition. In a joint report published today, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and the Corporate Mapping Project describe the impediments to moving away from fossil fuels in Eastern Canada based on a review of the region’s existing and planned fossil infrastructure. This post summarizes the main points of this study.

Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

The fossil fuel commodity chain in Eastern Canada

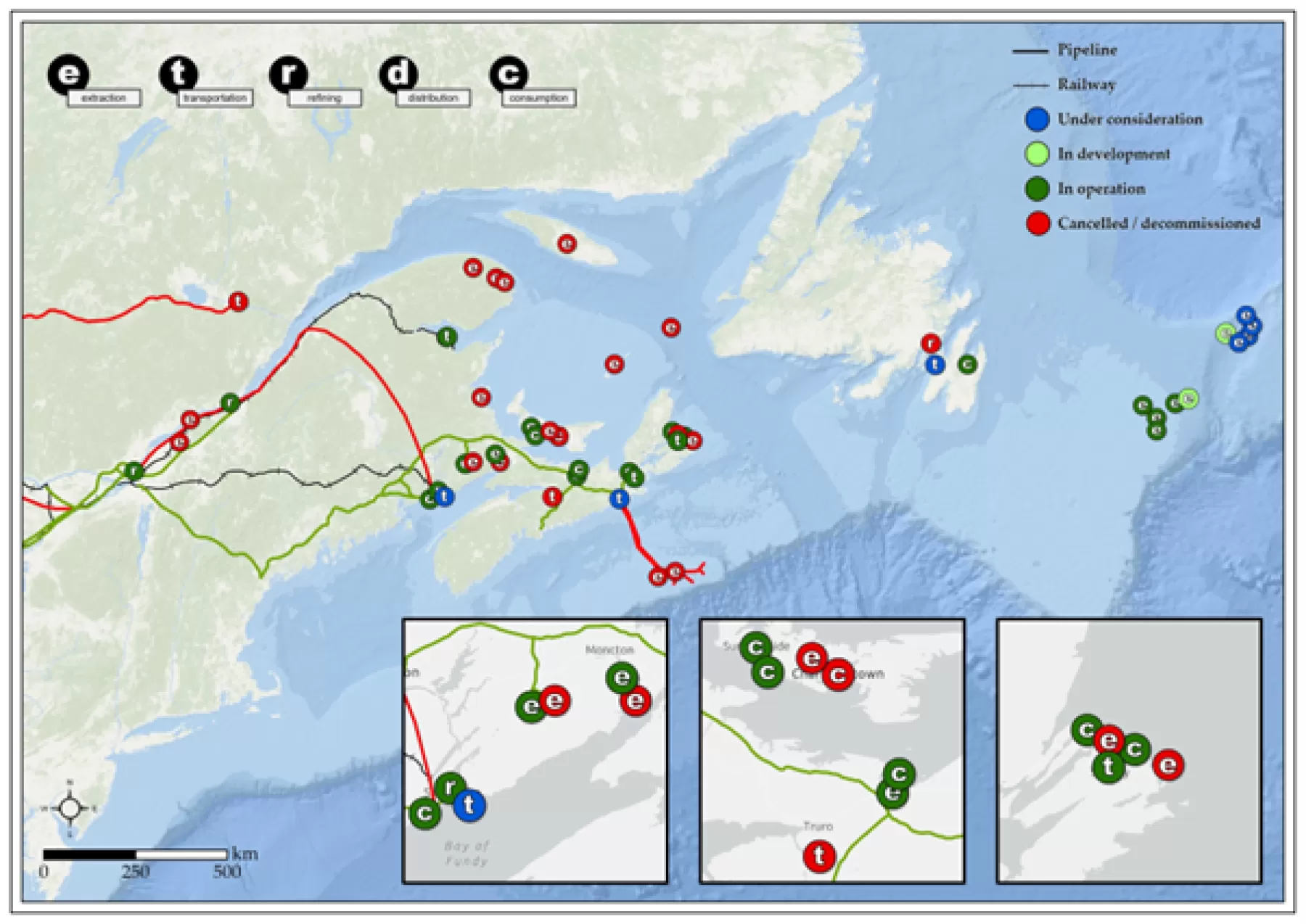

Thinking about fossil fuels in Canada immediately turns our minds to the Western provinces, where the extraction of 98% of fossil gas and 95% of oil in the country are concentrated. However, Eastern Canada also has its share of fossil facilities in each stage of the hydrocarbon sector, namely extraction, transportation, refining, distribution and consumption. Figure 1 maps the fossil infrastructure of this region.

Source: Darin Brooks et al., “Mapping Fossil Fuel Lock-In and Contestation in Eastern Canada.” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives – Nova Scotia, June 2023, p. 12.

Extraction: The province of Newfoundland and Labrador produces 95 million barrels of oil annually from offshore platforms, which is projected to increase with the Bay du Nord and West White Rose projects. Despite a strong protest movement in New Brunswick, the moratorium on hydraulic fracturing was partially lifted.

Refining: 37% of oil refining capacity in Canada is concentrated in the cities of Montreal, Quebec and Saint John (N.B.), to the tune of 672,000 barrels of oil per day.

Transportation and distribution: The St. Lawrence Valley is a major transport and export corridor by boat, train and pipeline. Enbridge Line 9 pipeline transports oil from Western Canada and the United States to the Suncor refinery in Montreal and the Valéro refinery in Lévis by ship. Part of this production is consumed locally, and the rest is exported through the Atlantic. The rail network also allows oil to be transported by train to the Irving refinery in Saint John. Quebec’s fossil gas distribution network of more than 12,000 km is another vital fossil asset, and the recent partnership between Hydro-Québec and Énergir for the dual-energy system and the management of winter peaks continues to be a source of debate in Québec.

Consumption: Finally, the majority of Nova Scotia’s electricity is produced by four coal-fired power plants, while 24% of New Brunswick’s electricity comes from fossil fuel sources. In Quebec, even though 98% of electricity comes from hydroelectric dams, half of the province’s energy needs still depend on fossil sources, primarily for transportation, industrial production and heating.

Carbon lock-in

All this infrastructure is associated with jobs, financial interests, and technologies, as well as systems of production and consumption, which, together, slow down the planning and implementation of a just energy transition. In this context, the term “carbon lock-in” appeared at the turn of the 21st century to describe how past investment decisions enabling major carbon infrastructure projects are delaying the transition. Corporate interests weigh heavily in this climate inertia. Starting at the end of the 1980s, strategies of obstruction are well documented: lobbying, greenwashing, disinformation, climate denial, and massive capital investments. Thus, when companies see their assets threatened by transition efforts, environmentally friendly public policies face significant pressure.

In this regard, the most recent federal budget represents a victory for the Canadian fossil fuel industry since its massive public investments are not intended to break with fossil fuels, but rather to green the industry’s image through technological mirages such as carbon capture and storage. Indeed, a quarter of the $80 billion in investments the federal government plans for the energy transition is dedicated to these technologies. Ottawa is thus contributing to the consolidation of the fossil fuel industry for decades to come.

Puzzling climate targets

All four Atlantic provinces and Quebec have net-zero targets by 2050, and even by 2040 in the case of Prince Edward Island. What is the value of these targets in a context where Newfoundland and Labrador intends to triple its oil production by 2047, where New Brunswick has partially lifted its moratorium on fracking, where the activities of the Donkin coal mine in Nova Scotia have recently resumed, and where Quebec’s Plan for a Green Economy only achieves at best 60% of its targets for 2030? Any climate target will likely conflict with powerful private interests, which must be identified and politicized. Otherwise, the climate objectives of the various levels of government will remain political decoys.

The report on carbon lock-in in Eastern Canada concludes with an inventory of environmental struggles waged since 2010 against fossil fuel projects. Faced with a set of false solutions promoted by industry and often taken up by policymakers – electric SUVs, hydrogen, carbon capture and storage, fossil gas, nuclear energy, etc. – environmental movements must fight not only for a move away from fossil fuels, but also against a techno-optimistic approach which touts the possibility of a transition without major transformations of our production and consumption systems.