The COVID-19 pandemic and associated policy response has caused an unprecedented economic shock in Canada. Millions of workers have lost their jobs, schools and workplaces have closed and everyone who can is staying home.

One consequence of this precipitous decline in economic activity has been a reduction in air pollution. Satellite images show dramatic improvements on some measures of air quality in major cities around the world. Reduced pollution may save tens of thousands of lives this year in China alone.

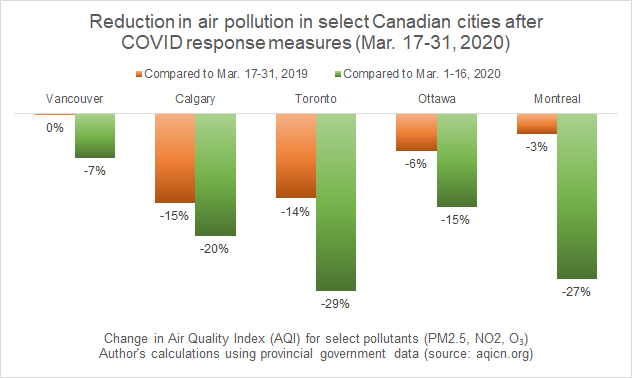

Pollution has declined in Canada, too. In the second half of March—roughly when shutdowns began and physical distancing measures went into effect—pollution levels in our five largest cities dropped between 7% and 29% compared to the first half of the month. Compared to the same period last year, pollution levels in the second half of March fell as much as 15%.

These changes are largely due to people staying home. The city of Ottawa, for example, has seen a 50% reduction in traffic volume and a 70-90% drop in transit ridership in the past few weeks. We can expect pollution levels to drop further as governments across the country ratchet up their COVID-19 response and even fewer people are moving around our cities.

Less pollution is a good thing, of course. Health Canada estimates that air pollution causes 14,600 premature deaths in this country every year. But Canada’s baseline air quality is actually quite good compared to other countries. Unlike in China, the brief respite offered by the COVID-19 lockdown in Canada will not save nearly as many lives as the virus will take.

How about Canada’s fight against climate change? Although they are not exactly the same thing, both air pollution (airborne substances that are hazardous to human health) and greenhouse gas emissions (airborne substances that trap heat inside the earth’s atmosphere) are produced by the combustion of fossil fuels. If pollution is declining, should we expect GHG emissions to drop as well?

The GHG emissions data are not reported as quickly as air pollution data so we can’t say for certain yet, but on this front we are likely to be disappointed for two reasons.

First, the COVID-19 lockdown thus far excludes many of the most emissions intensive sectors of the economy. Agriculture, heavy industry, electricity generation and oil and gas extraction, which collectively account for 57% of Canada’s emissions, are mostly continuing to operate during the pandemic (pending further shutdowns). Pollution from those industries doesn’t always choke up city streets but it still goes into the atmosphere.

Second, declining emissions in other sectors of the economy may not be as large as they seem. For example, although many offices are closed, home energy use, including wood fires and natural gas heating, will ramp up as people self-quarantine in the day. In the transportation sector, despite a drop in urban traffic, delivery services are picking up and trucking has yet to be disrupted.

Aviation emissions may crater, but domestic aviation does not account for a significant share of Canada’s emissions anyway. (Incredibly, international aviation emissions are not included in any country’s GHG inventory.)

In other words, the huge drop in economic activity during this period, which may be accompanied by a large drop in urban air pollution, is unlikely to produce a comparable drop in greenhouse gas emissions.

However, the more important question than the size of the drop is whether it will be a sustained drop over the long term.

All the historical evidence points to a rapid rebound in pollution once the economy is back on its feet. That was the global experience after the financial crisis and has been China’s experience since containing its coronavirus outbreak. But whether that occurs in this case will depend on the policy choices we make in the coming months.

This is not the time, for example, to bail out the struggling oil and gas sector, which needs to be phased out anyway. It is the time to transition those workers and communities to new industries.

This crisis presents an incredible opportunity for the economy to bounce back in a new direction. Although we all want to get back to normal as quickly as possible, there are some parts of “normal” that are better left behind.